|

|

Elizabeth

Custer |

||

|

Carde de visite of |

| Big

Horn County News March 30, 2006 Libbie Custer collection prompts plan for new Garryowen complex By

Carl Rieckmann In the first 100 years or so, thousands of pages written analyzing the military debacle focused largely on theorized details of the ill-fated attack on a huge renegade Indian gathering, on the golden boy’s dashing image and decisions, on Major Marcus Reno’s behavior and on follow-up vengeful Army expeditions that ended the free lifestyle of Indian bands. In

recent years, a more-balanced and appropriate picture of Indians defending

their families, homelands and way of life has emerged. |

He

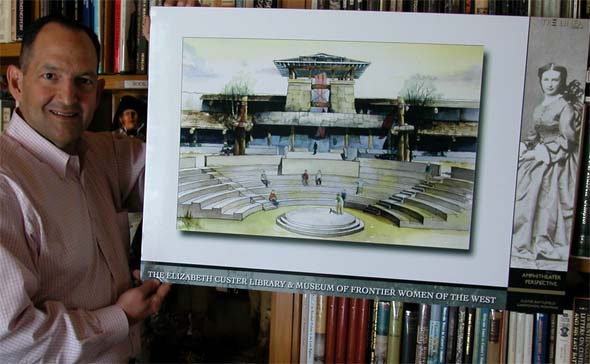

calls it “a magnificent national treasure” that needs a new archival

museum home to enable proper preservation and research activities. And to

follow his dream, he is prepared to level the existing museum and

commercial complex he built in the past decade at Garryowen to provide a

site for new construction. With recent endorsement of the local Custer Battlefield Preservation Committee, Kortlander has plans for a 56,000-square-foot Elizabeth Custer Library and Museum of Frontier Women of the West, a focal point for also telling the stories of other pioneering women. “My vision is to preserve an important piece of American history for future generations by creating an accredited depository where historical artifacts and documents will be housed for public review and scholarly research,” he says. “We hope to acquire additional collections and involve others who can enhance or contribute to the preservation of this segment of American history.” But what he has set in motion is bigger than his or the museum’s ability to complete without help of individuals and/or philanthropic organizations. He estimates needing $35 million to put up the new facility. “We have the location. We have the collection. We have the know-how. The only thing we’re lacking is the funding,” he asserts. The current museum building pales in size to demands of the new Libbie Custer collection for safe storage, display and research and of thousands of other items of Western Americana related to the Battle of the Little Bighorn already stored. “I have personally basically funded this without any federal funds for the last 10 years,” Kortlander says. “And now it’s the right time in history to construct an accredited depository to house the millions of dollars of manuscripts and artifacts we have acquired. But to do that, I need to find that one individual or corporation that will want to fund this project.” Pointing to U.S. National Park Service considering construction of a new visitor center at Garryowen to replace the small and antiquated one atop Last Stand Hill, Kortlander adds: “So what can be better than private citizens building the largest private museum in Montana at the most famous historical battlefield in the world?”

|

He

and associate Rhonda Elhard believe the worldwide appeal of the Custer

story and the plan to focus also on other frontier women should boost

interest in the project. Their research turned up no other “women of the West” museums, they note, so that aspect of the Garryowen concept appears to be a first. “I think that’s so exciting to me — there are so many lives to be focused on,” says Elhard. “(Libbie Custer)’s just the founding cornerstone.” In addition to the widow’s vast collection, Kortlander currently has such other artifacts as Annie Oakley photos, Calamity Jane’s shoes, Jeanette Rankin posters and references to Sacagewea on items relating to the Lewis and Clark trek. He notes Elizabeth Custer fits in this broadened concept because she was the first woman allowed to share her husband’s military quarters on the frontier. Looking ahead, Kortlander says pioneering women whose stories will be secured at the museum do not have to be famous. “Obviously, the men could not have made it without them,” he reflects. “They are an important part of (western history).” The founder acknowledges some controversy over any construction on the battlefield but points out he bought Garryowen as “a rundown gas station” and tomb of an unknown soldier. “What a better place to build a museum than on a place on the battlefield that was already commercially disturbed?” he asks. Kortlander also notes he has met the difficulties of running a museum at a national battlefield on an Indian reservation. “It’s kind of mind-boggling with all the government agencies and jurisdictional issues,” he suggests. “But I built Garryowen once, and I can build it again.” He credits Little Horn State Bank of Hardin with believing in his dream and helping to make it possible for him to purchase the Libbie Custer archive. “I have mortgaged myself to the hilt to try to bring this vision to a reality,” Kortlander acknowledges. |

With

his back up to the wall financially as he counts on funding for the new

center, he darkens when talking about holding together the Libbie Custer

trove, one of the largest of its kind in history. “I do not want to be the one responsible for scattering this collection to the world,” he offers. “If I were in this for monetary gain, I would not want the collection to be secured in a museum. This is all about preserving history and promoting tourism in one of the poorest counties in the nation.” Having studied Mrs. Custer’s will, Kortlander finds it interesting that this long-unknown group of mementos of the lives of her and her famous husband finally found its way to a battlefield museum, as was her apparent first wish — and still bearing the Custer name. He named his museum after Uncle Sam removed the Custer reference from the federal preserve in a more-general name-change to Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, which has housed another large group of Custer artifacts and papers secured by the government when it built the original battlefield monument after Mrs. Custer’s death, by terms of her will. “I am a neutral historian,” says Kortlander. “I used the Custer name because of its worldwide recognition.” Libbie Custer left leeway in her will as to what might be considered a George Custer “souvenir” and how items might be distributed — all to be “absolutely and finally determined by” her executor, National City Bank of New York, and “shall not be subject to review by any person or authority.” It’s unclear how the bank went about dividing up such items, whose historical significance then might have been viewed differently than current historical interest might dictate. Kortlander sees the collection acquisition and an eventual new complex as a major boon for Montana and the local area via heightened focus and visitation. “I think there are multiple doctorates setting in this collection,” he offers. “But first the museum needs to get funded.” |

|

Letter reveals nearness of kin fallen in battle By Carl Rieckmann |

It

includes a wide range of items, including: • bunches of letters to her and/or George from luminaries of the time; • black-bordered letters of consolation from generals and military widows; • most of Custer’s incoming correspondence during the Civil War and some afterwards, official and personal; • numerous manuscripts of her various observations and work relating to her Boots and Saddles book and other writings; • diaries and photographs of her extensive world travels in which she acted as an emissary on behalf of her country (“She was more famous than any First Lady,” notes Kortlander.); • some 300 newspapers 1863-1891 covering Civil War through Indian campaigns and Custer’s demise, considered one of the most complete newspaper archives on Custer and his military escapades; • 34 illustrations from artist/author William Reusswig’s book, A Picture Report of the Custer Fight; • photographic collection of and relating to Custer, including Indian leaders and scouts; • papers relating to her support of patriotic causes during World War I; • such various items as speech notes, railroad passes and rent payment receipts; and • all of her art book drawings before she married Custer when she dreamed of being an artist. |

Kortlander

is excited about finding the letter (and envelope) sent to Custer at Fort

Riley, Kansas, ordering him to face an examination board, which dumped him

out of the Army for about one year. If it still existed, and where, has

been a puzzle to historians, he notes. But little in the collection is likely to match the excruciating pertinence of Moylan’s October 1876 message to Mrs. Custer about four months after the debacle. “Do not think it strange that I have allowed so long a time to elapse since that terrible day, when you lost so many that were so dear to you and when I lost the best friend I have ever had, without writing to you,” he wrote to his shirt-tail relative. “I have often tried to do so but have failed every time; before commencing I could think of a thousand things to say, but when I tried to commit them to paper, they all forsook me; nothing remains but that one thing, that horrible fact that he was gone. “You will not think hard of me for not attending to the duty sooner, for if ever a man owed duty and faithfulness, I do to the widow of the man who from the beginning to the end was to me the best friend I ever had. “I cannot write of what I saw on the 27 of June when we went over to the field and buried the dead — it is unnecessary for me to say who the noble men were who were true to him to the last. They were the men of his own blood lying around him. There also was the Noble Cooke, Yates and Smith all lying close by the leader they all honored and loved so well. |

“Some

distance in the front was the cold clay of so gallant a man as ever lived

our Jim — I cannot say any more. A day will come, and thank God it is

not far distant, when Justice will be done (for) the dead of the Little

Big Horn.

“I hope to see you this

winter sometime; we expect to go east as soon as I can get away. (I?) send

love to yourself & our other friends. |

Elizabeth B. Custer

Library & Museum

"Frontier Women of the West"

Town Hall, P.O. Box 200

Garryowen, MT 59031

406.638.2000

Contact Us

Privacy:

Please note that any communications received by the Elizabeth B. Custer Library & Museum via electronic mail may become part of the permanent record of the library.